LGBT History Month: Sir Francis Bacon

For the third in our series of blogs written on the theme of this year’s LGBT History Month, ‘Science and Innovation’, Miles spotlights one of Islington’s most illustrious residents in the field of science, Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626), who is generally thought of as “father of the modern scientific method” and was homosexual.

Articles, blogs, and social media posts for LGBT History Month tend to focus on figures from the last few decades and occasionally stretch back into the last couple of centuries. This can largely be attributed to historic prejudice; people have only been legally able to declare their homosexuality in England and Wales since its decriminalisation in 1967. This bias is in some ways positive, as it allows us to celebrate figures from more familiar historical contexts, who people can easily relate to. However, it can give the misleading impression that queerness is somehow a modern invention, when it has always existed. Bacon’s brilliance and more distant “deviance” enables us to appreciate Islington’s queer heritage more completely.

Sir Francis Bacon was a multi-hyphenate; politician-lawyer-philosopher-author. He served as MP for various constituencies and Elizabeth I appointed him her Counsellor in 1591. Her successor James I appointed him Solicitor General in 1607, Attorney General in 1613, and Lord High Chancellor of England in 1618 – by 1618 he’d taken up residency in a pastoral manor north of the Thames, where Islington as we know it would one day be. He was by all accounts an extraordinary mind, an eloquent speaker, and shrewd strategist – qualities which allowed him to ascend to the highest public post in Stuart society.

Bacon held a lease on Canonbury House and Tower, which still exists in modern-day Islington, and was a tenant there from 1616-1625. In his day, it was a semi-rural manor with panelled rooms, tall views, surrounded by open fields, meadows, gardens, and farmland. Nowadays, it’s a stone’s throw from Highbury and Islington Station, near the bustling centre point of our borough (and very much worth a visit!). It’s a Tudor structure, and the oldest original building in Islington; the Charterhouse in Clerkenwell outdates it by some 200 years, but it was extensively rebuilt in the Tudor period.

Canonbury Tower

Bacon’s homosexuality was written about by people as wide-ranging as contemporary authors, puritan moralists, and even Bacon’s own mother, Lady Ann Bacon. She complained in a letter to her other son Anthony (who also, incidentally, was homosexual) about one of Bacon’s male favourites, ‘that bloody Percy’, whom her son kept ‘yea as a coach companion and a bed companion’. She complains of Bacon’s various pretty male attendants, Jones, Markes, and Enney: ‘his Welchmen one after another’ – Bacon, it seems, had a type.

The thrust of Lady Bacon’s complaint wasn’t that her son kept paid lovers in his employment (there were 25 male waiters listed in Bacon’s retinue of attendants at Canonbury House in 1918); it was that ‘bloody Percy’ occupied the master’s bedchamber, which offended her sense of decorum; he should have been sleeping in a lesser room, in accordance with his status. This underlines a tension apparent in Bacon’s sexuality: he lived at a time when “buggery” was punishable by death, but his homosexuality was seemingly public knowledge.

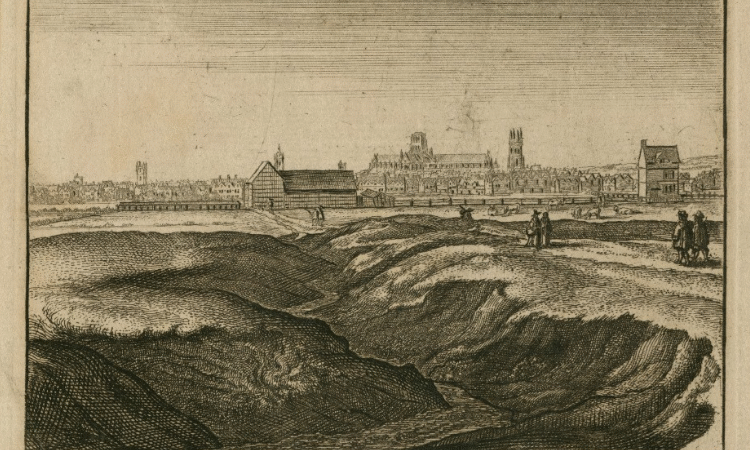

Engraving of Islington, looking south towards London, by Wenceslaus Hollar, C. 1640s. Image Courtesy of the Folger Digital Image Collection

Henry VIII enacted the Buggery Act in 1533, which outlawed the practice, but didn’t define it. In the following century, the law would be invoked most often for political reasons, to ensure a powerful man’s downfall. In fact, courtly systems of power allowed for and encouraged forms of homosocial and homosexual bonding, through systems of patronage – more powerful, typically older statesman would take younger, handsome men into their protection and control. Bacon left many of his favourites expensive gifts in his will – contemporary MP Sir Simonds D’Ewes condemned one such man as Bacon’s “catamite and bed-fellow”. He left nothing to his wife Alice Barnham (1592 – 1650), whom he married when she was 13 years old, and he was 45. The marriage was rumoured to be unconsummated.

Bacon’s expulsion from polite society in 1621 wasn’t on account of his gayness, but rather on charges of corruption. James I, Bacon’s close ally and another homosexual, dissolved Parliament that year, alienating himself from his people; it’s likely this played a significant part in Bacon’s ousting.

Bacon’s will to defy social convention in his sexual life carried over into his passion for science. In his writings, most of which were published towards the end of his life and during his period of exile post-1621, he argued for an approach to learning founded entirely on observation and inductive reasoning – not from reliance on doctrine, either scholarly or religious. He urged the adoption of a sceptical attitude to the world; doubting received knowledge, testing it, and improving upon it. In New Atlantis (1626) he imagined the first state-funded empirical research institution “Salomon’s House”, foreshadowing the formation of real-world scientific academies – hence his being thought of as the father of modern science. He supposedly died in the pursuit of knowledge: he went out in a blizzard to stuff a chicken with snow, testing if the cold had the same preservative effects as salt. He subsequently caught a “chill” and died; the snow preserved the chicken and killed him. There’s folklore that Highgate Pond in North London, the sight of the alleged stuffing, is haunted by a half-frozen chicken to this day!

Bacon’s writing is firmly impersonal and analytical. However, in his essays he explores topics like love, beauty, marriage, and friendship in ways which gesture towards his queerness. I’ll close with some extracts, and let them speak for themselves:

- Bacon wrote a seminal essay on beauty, and his ideal models are not women, but “August Caesar, Titus Vespasianus, Philip Le Bel of France, Edward the Fourth of England, Alcibiades of Athens, Ismael the Sophy of Persia, […] the most beautiful men of their times” – ‘Of Beauty’

- “A man hath a body, and that body is confined to a place; but where friendship is, all offices of life are as it were granted to him, and his deputy. For he may exercise them by his friend. How many things are there which a man cannot, with any face or comeliness, say or do himself? A man can scarce allege his own merits with modesty, much less extol them; […] But all these things are graceful, in a friend’s mouth, which are blushing in a man’s own.” – ‘Of Friendship’

- “although nuptial love maketh mankind, friendly love perfecteth it” – ‘Of Love’

John Vanderbank, Portrait of Francis Bacon.jpg

Latest Discover Islington blog

- Opening minds, expanding horizons 20 February 2026

- Celebrate World Book Day with Islington Libraries 20 February 2026

- Family help at your fingertips 19 February 2026

- LGBT History Month: Sir Francis Bacon 19 February 2026

- Marking International Women’s Day across Islington 16 February 2026

- Inside Shared Lives: carers share what they love about their job 13 February 2026