Victoria Cross memorial stones

Discover more about Islington’s heroes, awarded the Victoria Cross for bravery in the First World War, who were commemorated 100 years on during the centenary of the conflict.

Frederick Parslow

Mercantile Marine Master / Lieutenant Frederick Daniel Parslow V.C

Mercantile Marine Master Frederick Parslow (1856-1915) was a civilian when his ship, the unarmed SS Anglo-Californian, was ambushed by a German U-boat on 4 July, 1915.

He was killed in the attack, but not before managing to weave his ship back and forth across the North Atlantic, evading the attacking submarine.

The SS Anglo-Californian

At times during the battle the submarine came close enough for the Germans to fire rifles at the stricken ship. After Master Parslow was killed, his son, also called Frederick, took over the bridge as his father lay dead beside him on the deck, and continued the battle to save his ship.

Frederick Parslow Jnr

After an hour-and-a-half, two armed vessels reached the ship and rescued its surviving crew and its cargo of 927 horses bound for the Western Front.

Following the action, the Royal Navy gave Master Parslow a nominal rank of Lieutenant in the Navy Reserves after his death so that they could bestow upon him the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest military honour.

Master Parslow, who was born in Balls Pond Road, N1, was 59 when he was killed. He was the First World War’s oldest Victoria Cross recipient, and one of just two civilians to be given the honour during the conflict.

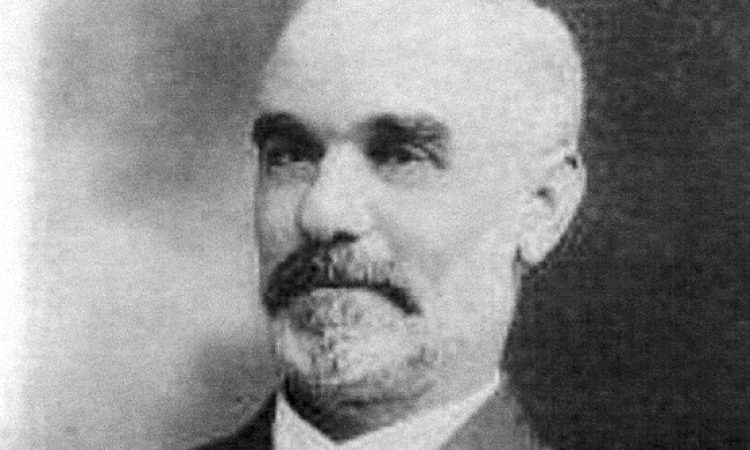

Frederick Booth

Frederick Booth (copyright IWM) V.C

Frederick Booth was born at 7 Davenant Road, Islington, on 6 March 1890. In February 1917 he was a sergeant in the South African Police, attached to the Rhodesia Native Regiment.

On 12 February 1917 he was involved in an attack on an enemy position in thick bush at Johannes Bruck, German East Africa, for which he would later be awarded the Victoria Cross.

Under very heavy rifle fire, he went forward alone to help a man who was badly wounded, and brought him back. He also rallied troops from his regiment who had become badly disorganised, and brought them back into combat.

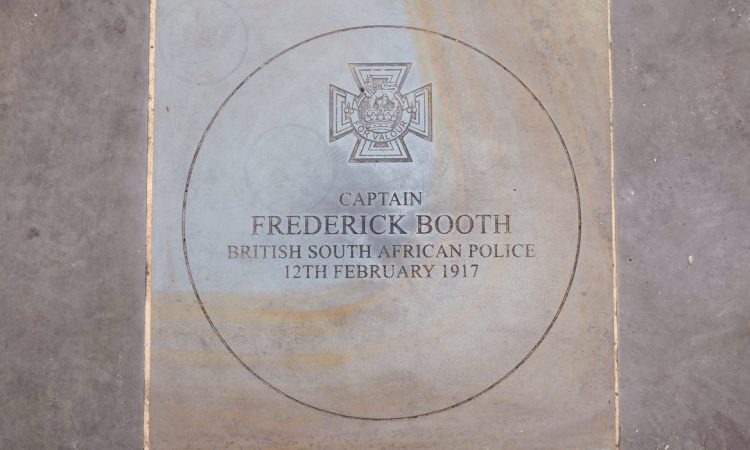

Victoria Cross memorial stone on Islington Green for Captain Frederick Booth

A supplement to the London Gazette on 8 June 1917, announcing his Victoria Cross award, said: “This NCO has on many occasions displayed the greatest bravery, coolness and resource in action, and has a splendid example of pluck, endurance and determination.”

Frederick Booth, who later attained the rank of captain, was awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal for further bravery in the First World War. He was later commissioned into the Middlesex Regiment and in 1939 served in the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps. He died in Brighton in 1960, aged 70, and is buried in Bear Road Cemetery, Brighton.

Charles Train

King George V investing Charles William Train with the Victoria Cross at the Second Army Headquarters. Blendecques, northern France, 6 August 1918 (IWM: Q9222)

Charles William Train was born at 58 Chatterton Road, Islington in 1890. He was educated at Gillespie Road LCC school, attended St Thomas’s Church and played in the church’s football team. He was later employed as a solicitor’s clerk at Gray’s Inn.

Train joined the London Scottish in 1909 aged 18 years and, following the outbreak of the First World War, arrived in France in September 1914, seeing action the following month. By 1917 he had become a corporal in the 2/14th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (London Scottish), of the British Army. Train later achieved the rank of sergeant.

Train was 27 years old when he was awarded the Victoria Cross for decisive action on 8 December 1917 at Ein Kerem, near Jerusalem, in Ottoman controlled Palestine.

His citation read:

“For most conspicuous, bravery, dash and initiative displayed under heavy fire when his company was unexpectedly engaged at close range by a party of the enemy with two machine guns and brought to a standstill.

Sergeant Charles Train (seated far right) with colleagues, 1918 (‘London Scottish Regimental Gazette’, Summer 1997)

Corporal Train on his own initiative rushed forward and engaged the enemy with rifle grenades, and succeeded in putting some of the team out of action with a direct hit. He then shot at and wounded an officer in command, and with bomb and rifle killed and wounded the remainder of the team. After this he went to the assistance of a comrade who was bombing the enemy from their front and shot at and killed one of the enemy who was carrying the second gun out of action.

His courage and devotion to duty undoubtedly saved his battalion heavy casualties and enabled them to advance to their objective at a time when the situation seemed critical.”

Charles Train emigrated to Canada in 1919 to pursue an agricultural scholarship. He was to make his mark, however, in shipping. He died in 1965 and is buried at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Burnaby, British Columbia.

His Victoria Cross is displayed at the London Scottish Regimental Museum in London.

John Sayer

Lance Corporal John Sayer V.C

John William Sayer was born at 50 Wellington Road, Islington on 12 April 1879. Shortly after his birth, his family moved to Ilford in Essex. He was the son of Samuel, a carman, and Margaret Sayer. John married Edith Maynard in 1904 and the couple went on to have four daughters and two sons. By 1909 John and his young family had relocated to Cricklewood, north London, were he ran a corn and seed merchant’s business.

At age 37 years, John enlisted in the army on 25 July 1916 and, as a machine gunner in the 8th Battalion of the Queen’s Royal (West Surrey) Regiment, he went to France a little over four months later. The following year he was promoted to the rank of Lance Corporal.

On the morning of 21 March 1918, when the much-anticipated German spring offensive began, John single-handedly seized and defended Shepherds Copse, a strategic position close to the Hindenberg line north-east of Le Verguier, northern France. He was wounded during the action, losing a leg. He died four weeks later in German captivity, aged 39.

John Sayer’s deed was witnessed by his platoon commander Lieutenant Claude Lorraine Piesse who, with Colonel Hugh Chevalier Peirs of the 8th Battalion of the Queen’s Royal West Surreys, recommended him for a Victoria Cross (VC). He was duly awarded the honour and his bravery citation below describes how, “for two hours on his own initiative and without assistance, he held the flank of a small isolated outpost and beat off a succession of attacks, inflicting heavy losses.”

His citation reads:

“For most conspicuous bravery, determination and ability displayed on the 21st March, 1918, at Le Verguier, when holding for two hours, in face of incessant attacks, the flank of a small isolated post. Owing to mist the enemy approached the post from both sides to within 30 yards before being discovered. Lance-Corporal Sayer, however, on his own initiative and without assistance, beat off a succession of flank attacks and inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy. Though attacked by rifle and machine-gun fire, bayonet and bombs, he repulsed all attacks, killing many and wounding others. During the whole time he was continuously exposed to rifle and machine-gun fire, but he showed the utmost contempt of danger and his conduct was an inspiration to all. His skilful use of fire of all descriptions enabled the post to hold out till nearly all the garrison had been killed and himself wounded and captured. He subsequently died as a result of wounds at Le Cateau.”

John Sayer’s actions on the day have been cited as having an immense effect on holding back the German offensive, which stalled, as they were held up by the Queen’s Regiment defence.

John’s VC was gazetted on 9 June 1919, some 15 months after the event. His widow Edith received her husband’s medal from King George V at Buckingham Palace on 16 November that year.

John Sayer is buried in Le Cateau Military Cemetery near Cambrai, northern France. His Victoria Cross is held with the Sayer family.

Frank Roberts

Major-General Frank Roberts V.C

Major-General Frank Crowther Roberts was born at 3 Hamilton Road, Highbury, Islington on 2 June 1891. He was the second child of Revd Frank Roberts, Vicar of St John, Southall and Sarah Roberts (née Barnes); he had two sisters named Edith and Rosa, the latter was also born in Islington. Frank married Winifred Wragg in 1932. They had no children.

Younger Frank Roberts was educated at St Lawrence College, Ramsgate and then at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, where he graduated in 1911 and was subsequently commissioned as second lieutenant into the Worcestershire Regiment of the British Army in March that year. With his battalion, Roberts was sent to Alexandria, Egypt the following year and was there upon the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. After returning to England, his battalion was sent to the Western Front and landed in France in early November.

Roberts was 26 years old, and an acting lieutenant colonel in the 1st Battalion, Worcestershire Regiment when, during the period 22 March/2 April 1918, west of Somme and at Pargny, France, he showed military skill in dealing with the many very difficult situations with amazing endurance and energy in inspiring all ranks under his command.

On one occasion the enemy attacked a village and had practically cleared it of British troops when, with an improvised party, Roberts led a counter-attack which temporarily drove the enemy out of the village, giving cover to the withdrawing British troops. The success of this action was entirely due to his personal valour and skill and for this he was awarded the Victoria Cross. His VC citation appears in the London Gazette dated 8 June 1918 and he was later presented with his medal in the courtyard at Buckingham Palace by King George V.

His citation reads:

“During continuous operations which covered over twelve days Lt -Col Roberts showed most conspicuous bravery, exceptional military skill in dealing with the many very difficult situations of the retirement, and amazing endurance and energy in encouraging and inspiring all ranks under his command. On one occasion the enemy attacked a village and had practically cleared it of our troops, when this officer got together an improvised party and led a counter-attack which temporarily drove the enemy out of the village, thus covering- the retirement of troops on their flanks who would otherwise have been cut off. The success of this action was entirely due to his personal valour and skill.”

Roberts was wounded on 27 March and treated at home. Returning to his battalion a few months later he, again, assumed command. He remained in this post for the rest of the war, leading the battalion during the ‘Hundred Days Offensive’ until the end of the conflict on 11 November 1918. During the First World War, he was wounded three times and was mentioned six times in despatches.

Roberts remained in the army after war, serving in Egypt and India. He retired from military life in December 1939, six months after his promotion to the rank of Major-General. He was the last living ex-member of the Worcestershire Regiment to be holding the VC at the time of his death in Derbyshire in January 1982.

Major-General Frank Crowther Roberts’s VC is displayed at The Worcestershire Regimental Collection in the Worcester City Art Gallery and Museum.

A total of five memorial stones will be laid in Islington as part of the national Victoria Cross Paving Stones project, funded by the Department for Communities and Local Government. Across the UK, paving stones are being laid in honour of each of the 627 men who were awarded Victoria Crosses between 1914 and 1918. Each stone is laid in the town where the recipient was born.

More Local History

- Barnsbury and Caledonian Road

- Archway and Tufnell Park

- Nag’s Head and Holloway

- Angel an Pentonville

- Bunhill and St Luke’s (Finsbury)

- Finsbury Park and Stroud Green

- Highbury

- Clerkenwell

- Islington Central and Canonbury

- Newington Green

- Victoria Cross memorial stones

- Streets with a story

- Islington during the First World War

- Islington and Holloway Fire Stations

- Society of Genealogists

- D-Day (1944-2019)

- Highbury Corner V-1 bomb

- Italians in Islington

- Islington on the Home Front during the Second World War

- Islington’s Pride: Our heritage, our future

- Islington as a Place of Refuge

- Barging Through Islington: 200 Years of the Regent’s Canal

- A short history of waste and recycling in Islington

- Gay Liberation Front at 50